How the noodles invented by China China are popular in Japan?

Historically, rice once occupied a supreme position in Japanese life. The Japanese once thought that food was rice, and eating rice was nothing more than adding salt. There is even a saying in Japan that "rice is rich in salt" means that as long as there is rice and salt, there is life. But now, according to a survey conducted by NHK (Japan Broadcasting Association), "Ramen (Lamian Noodles)" has become the Japanese favorite food in the New Year-noodles have reached the top of food in this rice country.

Why didn’t ancient Japanese eat wheat?

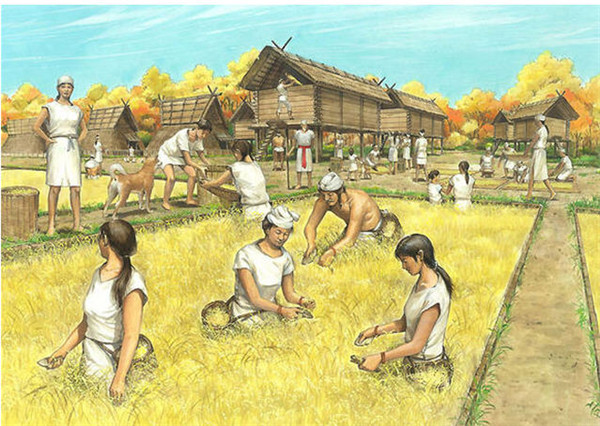

There is a folk legend in Japan that "the fox stole an ear of rice from China and took it back to Japan in a bamboo tube", so that Japan had rice. Through this legend, we know that Japanese rice culture was spread from China, and there are two ways to spread it: first, it passed through Jiangsu and Shandong, and crossed the sea from Shandong Peninsula to the south of the Korean Peninsula; The other is introduced into the northern part of the peninsula by land from North China to Northeast China, and then spread to the south. Both reached the same goal by different routes, and spread to Japan through Ma Haixia. This can be seen from the early remains of paddy fields in Japan-archaeological discoveries in the coastal area of Fukuoka in the northern part of Kyushu Island, which is closest to the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula. Subsequently, the rice cultivation technology gradually spread to the south and east with the northern part of Kyushu as the center. By the 3rd century AD, it had spread to Shikoku Island and most parts of Honshu Island. The grains unearthed in the sites of Yayoi and Gufen from the 3rd century BC to the 7th century AD were all rice.

Sites of ancient tombs

Yayoi era imagination map

Because the water and heat conditions in the Japanese archipelago are suitable for rice planting, and compared with planting coarse cereals in dry fields, rice planting is labor-saving, time-saving and high-yield. Therefore, for thousands of years, Japan’s rice production has been the first of all kinds of crops. Therefore, the Japanese call rice the king of food, and rice is a gift from heaven to Japan. Japanese people are used to eating rice, so in the history of ancient Japanese agriculture, barley and wheat are rare. In ancient Japan, people even thought it was time-consuming to eat pasta, but the saying that "the poor eat wheat" was repugnant to pasta. Although in famine years, Japanese officials often encourage the cultivation of wheat to alleviate famine and distribute seeds; However, farmers refused to buy it. Even if they were forced by the government to plant wheat, they refused to eat it as food. Instead, they cut it before it matured and sold it as horse feed, so that the Emperor had to issue a decree in 715 AD announcing that if the immature wheat was sold as horse feed, it would be severely punished.

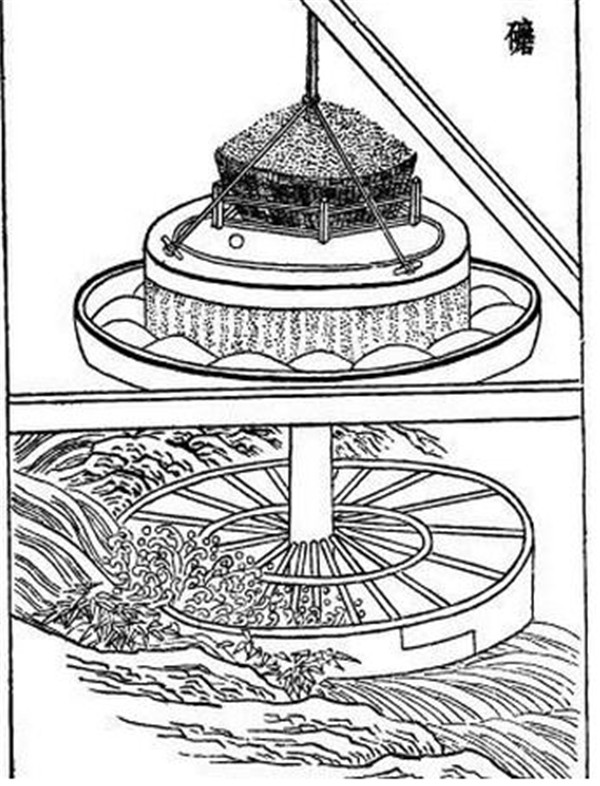

Is it really that the taste of wheat doesn’t agree with the Japanese? In fact, it is not. The fundamental reason for boycotting wheat planting is actually that Japan lacked the technology to make flour at that time. Before the era of mechanized mass production, ancient people used a stone mill to make flour. In China during the Sui and Tang Dynasties, firstly, the stone mortar was pushed by human or animal power to process flour, and then the flour was milled by water truck, thus reducing the price of flour, making it possible for ordinary people to eat pasta, and thus making pasta appear and popularize in large numbers. According to the Japanese history book "The Book of Japan", as early as 610 AD, a Koguryo monk named Tanzheng brought the stone mill to Japan, but the Japanese couldn’t copy it. To make a stone mill, it was necessary to carry out precision processing on hard stones. However, the stonework technology in ancient Japan was underdeveloped, and it was really beyond their power to produce the stone mill. At that time, Japanese people could only grind flour with wooden mortar and pestle, but wooden mortar and pestle were only suitable for pounding rice. When wheat with hard bran was encountered, it was quite laborious to pound it, and it became very difficult to make pasta. Unlike wheat, which needs to be ground into powder to eat (the seed coat of wheat is hard, so it is very unpalatable to eat it directly), millet can be cooked directly as long as it is washed, and even eating brown rice unexpectedly makes up for the vitamins and minerals that Japanese people lack in their daily diet. After the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese army generally ate polished rice, but beriberi caused by vitamin deficiency appeared on a large scale. As a result, contrary to the folk saying that "the poor eat wheat", for a long time,Japanese pasta has become a kind of precious food monopolized by officials, nobles and senior monks.

Traditional style stone mill

Plain noodles, udon noodles, buckwheat noodles

When it comes to pasta, we can’t help but mention noodles. In 2002, in the Qijia cultural layer of the Neolithic age in Qinghai Province (the Neolithic culture in Gansu Province from 2200 BC to 1600 BC), archaeologists unearthed noodles made of millet and millet 4000 years ago, which were about 50 cm long and 0. 3 cm wide, even in thickness and bright yellow in color. This is probably the earliest known noodles. China’s invention right of "noodles" is therefore beyond doubt.

Ancient noodles unearthed in Qinghai

Before the Tang Dynasty, all foods made of wheat flour were called "noodles", and foods such as noodles, which were heated by putting wheat dough in boiling water, were called "soup cakes", but in the Song Dynasty, "noodles" were separated from "cakes" to refer to "noodles" exclusively. In Meng Liang Lu, written by Wu Zimu, which describes the bustling scene of Lin ‘an (now Hangzhou) in the Southern Song Dynasty, a noodle shop has been set up, including "silk chicken noodles", "three fresh noodles" and "fried chicken noodles", which is no different from today.

Although there was no communication between China and Japan at the national level in Song Dynasty, the cultural and economic exchanges between the two sides were still frequent. Different from the official "envoys to the Tang Dynasty", Japanese monks who entered the Song Dynasty played a vital role in the exchanges between the two sides. At that time, when Zen Buddhism was flourishing in China, most Japanese monks also wanted to study in China. While introducing Zen Buddhism to Japan, they also brought back the food culture of China monasteries at that time (all vegetarian, of course), and noodles were one of them. Some people in later generations concluded that "most epoch-making Japanese food comes from monasteries and is generally spread by monks who have experience in studying in China".

In 1241 AD, the founder of Tofuku-ji Temple in the south of Kyoto today, Shengyi Kunshi, returned from China and brought back a "water mill map" (a design of a mill made of waterwheels and gears), which finally made Japanese flour-making technology catch up with China’s level. From then on, Japanese people can taste pasta, which used to be exclusive to monks and nobles, and gradually change their views on pasta.

Schematic diagram of water mill

Kyoto Tofuku-ji Temple

What noodles did the ancient Japanese eat? The first thing that was welcomed by the Japanese was Su (Suo) noodles. Vegetarian noodles are the earliest Japanese noodles. At that time, the vegetarian noodles were all stretched by hand after the dough was kneaded repeatedly, just like the handmade Lamian Noodles, which was characterized by being long and thin, refreshing to eat, and mainly used as cold food. Next came the famous udon noodles, which were made by slicing thin dough into hot soup noodles. It is said that the troops of Takeda Shingen, the famous "Tiger of Jiafei" in the Warring States Period, used udon noodles as their food for marching. It stands to reason that udon noodles can only be made by rolling the dough thin with a rolling pin and then cutting it with a knife. Unlike making vegetarian noodles, it takes high technology to pull the dough into long strips first, but in fact udon noodles appeared in Japan as late as the 15th century. Investigate its reason, it is because the technical level of the Japanese at that time was too poor to make a chopping block! It takes a planer to make a chopping block, but it didn’t become popular in Japan until the Edo period in the 16th century. Before that, workers needed to put the blade on the front end of the stick and flatten the wood bit by bit to make a chopping block, which was very laborious.

The buckwheat noodles appeared later than udon noodles. Buckwheat itself is not sticky and easy to break, so it is not suitable for making noodles. Legend has it that in 1659, Zhu Shunshui (1600-1682), a adherent of the Ming Dynasty who stayed in Mitofan (now Ibaraki Prefecture), taught the Japanese to mix wheat flour into buckwheat flour to make it sticky and elastic, so this kind of noodle called "the most Japanese characteristic" came out. One of the reasons why soba noodles are popular is to win the favor. It is said that Japanese gold foil masters, at work, often use soba dough to touch the gold foil fragments that take off and fall everywhere. To this end, Japanese folks think buckwheat is a cash register item, so they use its auspicious saying to prepare buckwheat noodles when they are engaged, married or celebrating. Eating buckwheat noodles every other year on New Year’s Eve is also for good luck, hoping for gold and silver to enter the home, which is a mentality with China’s "more than fish every year". By the 19th century, Edo (now Tokyo), a city with a population of 1 million, had a list of 100 buckwheat noodle shops, which showed the Japanese people’s enthusiasm for this kind of noodle at that time.

Japanese udon noodles

Japanese buckwheat noodles

The Birth of "Lamian Noodles"

The same is noodles, whether udon noodles or buckwheat noodles. An important difference between Japanese noodles before modern times and Chinese noodles is that Japanese noodles are made without adding alkaline water. When wheat flour meets water, it will produce a grid-like tissue, commonly known as "gluten". Alkaline water is a kind of alkaline natural soda water containing potassium carbonate and sodium carbonate. When Chinese noodles are made, alkaline water is added, so the kneaded dough can change the protein in flour, enhance the viscosity and elasticity, and make the taste more comfortable.

正宗的中国面条迟至19世纪末、20世纪初才进入日本。1893年时,日本横滨的外国人居留地中居住着约5000名外国人,其中中国人约为3350人。而在甲午战争之后,清朝开始向日本派遣官费留学生,以后自费留学生的规模也急剧扩大。在1905年前后,在日本的中国留学生人数达到大约5万人。与此同时,无论是梁启超这样的立宪派,还是孙文这样的革命党,都将日本作为重要的活动据点,如此众多的中国人在短时间内来到日本,势必又一次将中国的饮食文化带入东瀛四岛。

大约在20世纪初期,中国面条出现在了横滨的“南京町(唐人街)”,并从这里出发,迅速征服日本人的脾胃。值得注意的是,当时的日本一心脱亚入欧,断发易服之外,连饮食也恨不得一日西化,著名思想家福泽谕吉撰文鼓吹要像西洋人一样“应该吃肉”(此前受佛教影响,日本人几乎不吃鱼肉之外的肉类)。明治天皇带头喝牛奶吃牛肉,当时的日本宫廷膳食干脆就是法式大餐。相反,对于传统的文化母国,日本则是一副鄙薄心态,印度古籍用于指代中国的“支那”一词正是在这一时期,在日本人的口中出现了贬义。在这样的背景下,中国面条在日本的传播,完全是出自食物本身的魅力。

普通的中国(苏州)羊肉面

横滨唐人街

尽管这种中国面条毫无荞麦的成分,但比起粗粗圆圆的乌冬面,形式上更接近固有的细长的荞麦面,被日本人称为“南京荞麦面”,并以其价格低廉、滋味鲜美而受到日本中下层市民的欢迎,逐渐走出“唐人街”,在日本主流社会中流行开来,名字也变成了“支那荞麦面”。第二次世界大战之后,迫于作为战胜国的中华民国政府的压力,日本官方不得不下令禁用“支那”一词。结果,不知从何时起,“支那荞麦面”又变成了“ラーメン”。这个假名的读音“ramen”极似普通话的“拉面”,显系晚近从汉语里直接借入的外来词。

(Japanese) ramen

Lamian Noodles has become a national delicacy in Japan today, mainly because the long Lamian Noodles can be matched with various vegetables and animal meat as the main materials, and seafood such as soy sauce, ginger, onion, sesame oil and various scallops or shrimps can be added to meet the dietary needs of all social classes. Therefore, there is a "Chinese Noodle Noodle Center" in Fukuoka, a "New Yokohama Lamian Noodles Museum" in Yokohama, and even a "Japan Lamian Noodles Research Association", which specializes in Lamian Noodles magazine … Lamian Noodles has become a well-deserved king of Chinese cuisine circulating in Japan.

The scene of eating Lamian Noodles in the cartoon "Chess Soul"

References:

(Han) Li Xuzheng et al. Translated by Hong Weiwei: The Road of Noodles: A Wonderful Diet Inherited for 3,000 Years, Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press, 2013.

Xu Jingbo: The East Wind Blows from the West: Chinese Culture in Japan, Yunnan People’s Publishing House, 2004.